Efforts to resolve the ongoing war in the Middle East inspire cautious optimism, yet observers remain largely skeptical: the Arab–Israeli conflict has roots that reach far too deep, and many have grown accustomed to the idea that every truce will, sooner or later, give way to a new escalation. However, there are precedents of centuries-long enmities ending once and for all. One of the most striking cases is the hostility between France and Germany, which lasted from the Middle Ages through the end of World War II, after which the two countries came to their senses and not only abandoned the policy of weakening one another, but even chose to build common institutions that eventually gave rise to an integration project which, over time, evolved into the European Union.

Content

Contact established: the meeting in Caux

How former bitter enemies invented European integration

Diplomacy of leaders: the Adenauer–de Gaulle tandem

From the monetary union to the handshake at Verdun

German reunification and German tanks in Paris

Who is the enemy now? Sociology of relations

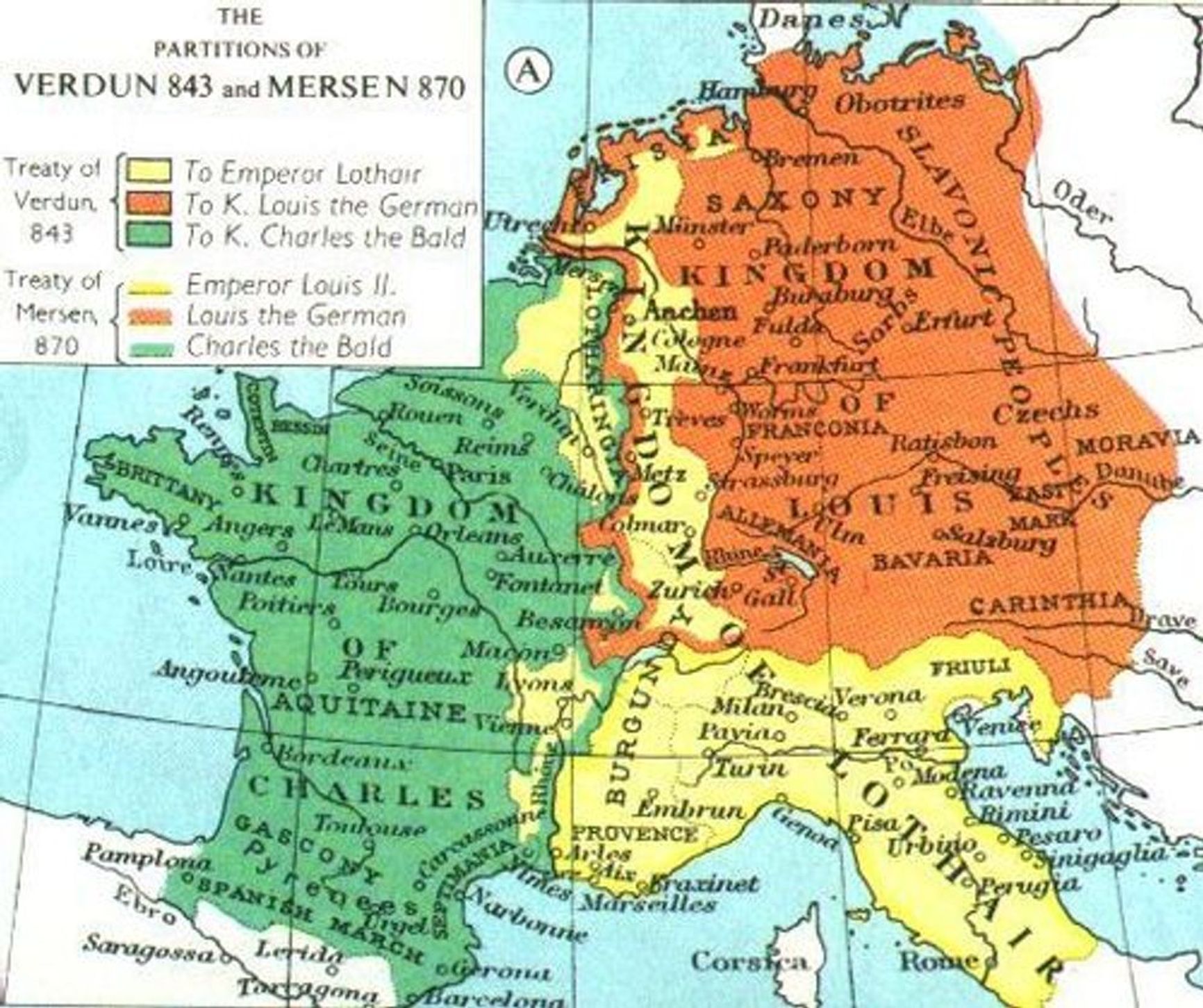

After the death of the “Father of Europe,” Charlemagne, in the year 814, the empire he had built fell apart. In the west arose the Frankish Kingdom, the future France, and in the east the East Frankish Kingdom, the future Germany. Between them lay Lotharingia with Alsace — rich and strategically vital lands. It was largely over these territories that France and Germany quarreled and fought for the ensuing centuries.

Map of the Carolingian Empire founded by Charlemagne

Two countries repeatedly clashed in major wars — the Thirty Years’ War, the Wars of the Spanish and Austrian Successions, and the Seven Years’ War. For a decade in the early 1800s, Napoleon brought much of western Germany under his control, spurring the rise of German national consciousness and leading to the Wars of Liberation of 1813-1815.

Throughout the 19th century, the rivalry deepened. Its culmination came in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, which ended in France’s defeat, the proclamation of the German Empire in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, and the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine by Germany. This act of humiliation gave rise to a powerful movement of revanchism in France, which for decades afterwards shaped its foreign policy.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the confrontation took institutional form in the system of military alliances — the Triple Alliance and the Entente — which directly led to the First World War. On that war’s Western Front, including at Verdun, millions of French and German soldiers perished in ferocious trench battles.

During the Second World War, France suffered a swift defeat and fell under Nazi occupation. A collaborationist Vichy regime was established in the country, opposed by a Resistance movement that fought against the Germans and their allies. French Jews became victims of the Holocaust, with tens of thousands deported to death camps. These events further deepened the animosity between the two nations.

Contact established: the meeting in Caux

Immediately after the Second World War, while Europe still lay in ruins, the first steps toward Franco-German reconciliation were taken not by governments, but by civil society organizations. One such movement was Moral Re-Armament (MRA), founded by the American pastor Frank Buchman in the 1930s. He believed that true peace required not only new political institutions but also the moral renewal of individuals.

After the Second World War, the first steps toward Franco-German reconciliation were taken not by governments but by civil organizations

After 1945, MRA supporters concluded that Europe could not recover without dialogue between former enemies — the French and Germans chief among them. To foster this, they purchased a former hotel in the Swiss village of Caux and turned it into an international meeting center.

In the summer of 1946, the first delegations from France and Germany gathered there. The French side included former members of the Resistance, along with politicians and other public figures. Irène Laure, a socialist and member of parliament whose son had been tortured to death by the Nazis, stood out among them. Her hatred toward Germans was so intense that she initially wanted to leave upon seeing the German delegation. But during the meeting, she met Clara von Trott, widow of the German diplomat Adam von Trott, one of the conspirators in the plot against Hitler who had been executed in 1944. In their conversation, Laure unexpectedly confessed her hatred and openly asked for forgiveness, while her interlocutor acknowledged Germany’s guilt for its crimes.

From the German side came young intellectuals, students, and future politicians — those whom the American and Swiss organizers saw as the “new generation,” capable of demonstrating that Germany had changed. Later, Irène Laure traveled across Germany giving lectures on reconciliation, and cultural exchanges organized by the MRA began to lay the groundwork for official dialogue. Yet these early efforts could not immediately alter state policy. France and Germany still faced a long and difficult path toward mutual understanding.

How former bitter enemies invented European integration

In the decade following the end of the Second World War, French policy toward Germany evolved from a desire to weaken and control its former foe to a willingness to cooperate within European and trans-Atlantic frameworks. The defeat of the Third Reich, the dismantling of the Nazi regime, and the trials of war criminals could not in themselves produce reconciliation. Rather, they marked the starting point from which Franco-German relations would develop throughout the second half of the twentieth century.

French soldiers in Berlin, 1946 Deutsche Fotothek

In 1945, Germany was divided into four occupation zones. France, which controlled the southwestern zone, proceeded from the idea that Germany must be disarmed — militarily, economically, and financially. Yet the French administration also acted pragmatically: in many cases, it turned a blind eye to the biographies of certain German officials, provided that their expertise could be useful for governance or economic reconstruction. (The Insider covered this issue in greater detail in the article “The Nazi factor: How West Germany democratized without fully purging its Hitler-era civil service.”)

Still, Paris sought to limit the development of heavy industry in Germany while consolidating control over the coal and steel of the Ruhr. Special attention was given to the Saar region, which France effectively removed from the German economy and brought under its own influence.

By 1946-1947, it had become clear that the Allies differed sharply in their visions for Germany’s future. The United States and the United Kingdom increasingly prioritized reconstruction over punishment, recognizing that without a revived German economy, Europe itself could not recover. They merged their zones into the so-called Bizone, slowed down the dismantling of factories, and increased the domestic use of German coal.

Initially, France resisted this course. However, the American Marshall Plan and the creation of the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC) in 1948 gradually drew West Germany into the Western European economic system. Paris now faced a crucial choice: either continue focusing on reparations and control, or participate in the new project of European integration.

Paris faced a choice: continue pursuing reparations and control, or join in the integration of Europe

With the escalation of the Cold War, the Soviet imposition of the Berlin Blockade, and the creation of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) in 1949, French policy began to shift. The Petersberg Agreement of that same year preserved international oversight of the Ruhr, but it was already clear that keeping Germany “down” was no longer feasible. Instead, it would have to be brought into Western institutions.

From this changing reality emerged the Schuman Plan of 1950, an initiative proposing the creation of a common market for coal and steel among France, Germany, Italy, and the Benelux countries. The treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), signed in 1951, marked the beginning of a new French strategy: to control Germany not from the outside, but through shared supranational institutions.

The question of security proved the most difficult. The Korean War (1950) demonstrated that Western defense would be difficult without German troops. France was categorically opposed to reviving a German national army and proposed a compromise: the creation of a European Defense Community (EDC), under which German contingents would be subordinated to a supranational command. Chancellor Konrad Adenauer agreed to the plan in principle, but insisted on full equality. The treaty was signed in 1952, yet the project provoked strong opposition in France, and in 1954 the National Assembly refused to ratify it — a major blow to those hoping for a “European Army.”

A solution was soon found in another format: the Paris Agreements of 1954 granted West Germany almost full sovereignty, brought it into the Western European Union, and opened the way for its accession to NATO. In May 1955, the Federal Republic of Germany became a full member of the North Atlantic Alliance. Germany had returned to the Western community, but within institutional frameworks that allowed Paris to act not as a bystander, but as an equal partner.

Within just a decade, French policy toward Germany evolved from one of punishment and control to one of integration and cooperation. If in 1945 Paris still hoped to detach the Ruhr and the Saar, by 1955 France and Germany were already jointly building supranational European structures and accepting Germany’s participation in NATO. This shift was not merely a foreign-policy adjustment — it was a decisive step toward what would later be known as Franco-German reconciliation.

However, even in the mid-1950s, this process was neither smooth nor unequivocal. After Stalin’s death and the collapse of the European Defense Community project, hopes for deep military integration faded, and French policy once again oscillated between Atlanticism and the pursuit of an independent European role.

The Suez Crisis of 1956 exposed the limits of France’s ability to act alone and reinforced the perception that Paris needed an alliance with West Germany to strengthen its own geopolitical position. Meanwhile, France was entering a period of domestic turmoil: the Algerian War, frequent cabinet changes, and the chronic instability of the Fourth Republic undermined public confidence in the existing regime.

Diplomacy of leaders: the Adenauer–de Gaulle tandem

It was in this context that, in June 1958, General Charles de Gaulle returned to power with promises to restore order at home and conduct a more independent and influential foreign policy abroad. To achieve this, he believed it essential to rely on a partnership with the Federal Republic of Germany.

The leaders of the two countries met in the autumn of 1958 in Colombey-les-Deux-Églises, where de Gaulle proposed establishing regular intergovernmental consultations. On the German side, Konrad Adenauer supported the idea that European policy should not merely follow the line set by the United States. From that point on, the two began holding regular telephone conversations, exchanging personal messages, and urging their governments to seek common positions on issues concerning Berlin, Europe, and NATO.

This personal diplomacy proved effective: during the Berlin Crisis, de Gaulle refused to compromise with Moscow, thereby strengthening Adenauer’s trust in Paris. Together they built the foundation of their future tandem — a habit of consultation and a sense of political closeness before taking action.

In 1962, the two leaders elevated their friendship to the intergovernmental level. Adenauer visited France, where both took part in a joint mass at Reims Cathedral, the traditional site of French royal coronations and a powerful symbol of the devastation of the First World War. With this gesture, they invited their nations to reconciliation and affirmed the idea that the memories forged in an adversarial war could be transformed into a political alliance.

Charles de Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer, Paris, 1963

Bundesarchiv

During his return visit in September 1962, de Gaulle delivered speeches in German in Bonn and Cologne, thereby demonstrating respect for the German public. At the same time, both sides agreed to “mobilize human capital” — by promoting school exchanges, partnerships between cities, and the establishment of youth camps — and to elevate these initiatives to the level of state policy. These steps strengthened the personal trust between de Gaulle and Adenauer and laid the groundwork for a future treaty of friendship between France and the Federal Republic of Germany.

In January 1963, de Gaulle and Adenauer signed the Élysée Treaty in Paris. Though only six pages in length, the document formalized on paper what had previously rested on the personal commitments of the two leaders.

The treaty established a rule of regular contact: two summits of heads of state per year, several meetings of foreign and defense ministers, and permanent consultations between military staffs. This framework required both governments to coordinate their positions in advance on major issues — ranging from NATO policy and relations with the United States to European integration.

Special emphasis was placed on culture and youth. The treaty created the Franco-German Youth Office, jointly managed and funded by both governments. Thanks to this initiative, millions of French and German students participated in exchanges. Later, additional mechanisms were added, including national coordinators for bilateral cooperation and a German Commissioner for Cultural Affairs. All of this helped sustain a steady course toward rapprochement — not only at the level of formal diplomacy, but also in the everyday lives of citizens.

In short, the personal friendship and mutual trust between de Gaulle and Adenauer became the foundation for a durable system of relations between their two nations. The Élysée Treaty not only consolidated the movement of France and Germany toward reconciliation, but also made them the principal driving force of European integration.

From the monetary union to the handshake at Verdun

After de Gaulle’s departure in 1969, France’s policy became less national in focus and more open to cooperation within Europe. At the same time, West German Chancellor Willy Brandt launched his “new eastern policy” (Ostpolitik), signing treaties with the USSR and Poland and establishing relations with the Soviet-dominated German Democratic Republic. Paris initially feared that Germany might become too independent, but President Georges Pompidou ultimately supported Brandt. He maintained that détente could succeed only if Europe was strong and united.

In the 1970s, Franco-German rapprochement was further strengthened by President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing and Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. They were of the same generation, both had backgrounds in finance, and the two peers quickly established a personal rapport. Their friendship facilitated progress on initiatives that went beyond the Élysée framework. It was d’Estaing and Schmidt who, in the late 1970s, developed the idea of a European Monetary System, which in 1979 became an important step toward the later introduction of the euro as a single currency.

During this same period, the world faced oil crises, but rather than retreating into economic isolation, France and Germany sought to find joint solutions. In 1975, at their initiative, the first G7 summit was held in Rambouillet, where global financial issues were discussed. Although differences between the two countries remained with regard to economic policy, both sides endeavoured to demonstrate an example of coordinated action.

Helmut Kohl and François Mitterrand, Verdun, 1984

Getty Images

In the 1980s, the focus shifted to the efforts of French President François Mitterrand and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl. Their cooperation extended not only to economic and security matters but also to addressing the traumas of their shared past. In 1984, the two leaders visited Verdun, the site of the horrific battles of the First World War. Mitterrand and Kohl stood side by side and held hands in front of the graves of fallen soldiers. This gesture became a symbol of reconciliation — former enemies demonstrating that they were now allies, sharing a common responsibility for Europe’s future.

German reunification and German tanks in Paris

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, the topic of German reunification elicited both joy and concern among European leaders. At a special summit in Paris on Nov. 18 of that year, President Mitterrand convened the heads of government of the European Community. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher openly insisted on maintaining the status quo and spoke of the risks associated with the return of the “German question.”

Similar concerns were voiced by representatives of other countries, such as the Netherlands and Italy. As Chancellor Helmut Kohl later recalled: “Distrust of us, the Germans, returned. Now Germans are speaking again of [their] own unity; now they are less interested in Europe. Old fears that Germany was becoming too strong have resurfaced.”

Mitterrand also did not immediately embrace the idea of rapid reunification. He was concerned that a strong Germany could overshadow France in Europe. However, he recognized that the process could no longer be stopped. Gradually, the French position shifted from restraint to support — provided that reunification proceeded hand in hand with deeper European integration. This is why, in the early 1990s, Germany and France actively promoted the idea of a political and monetary union, an intermediate step on the road to the creation of the European Union and the introduction of the euro.

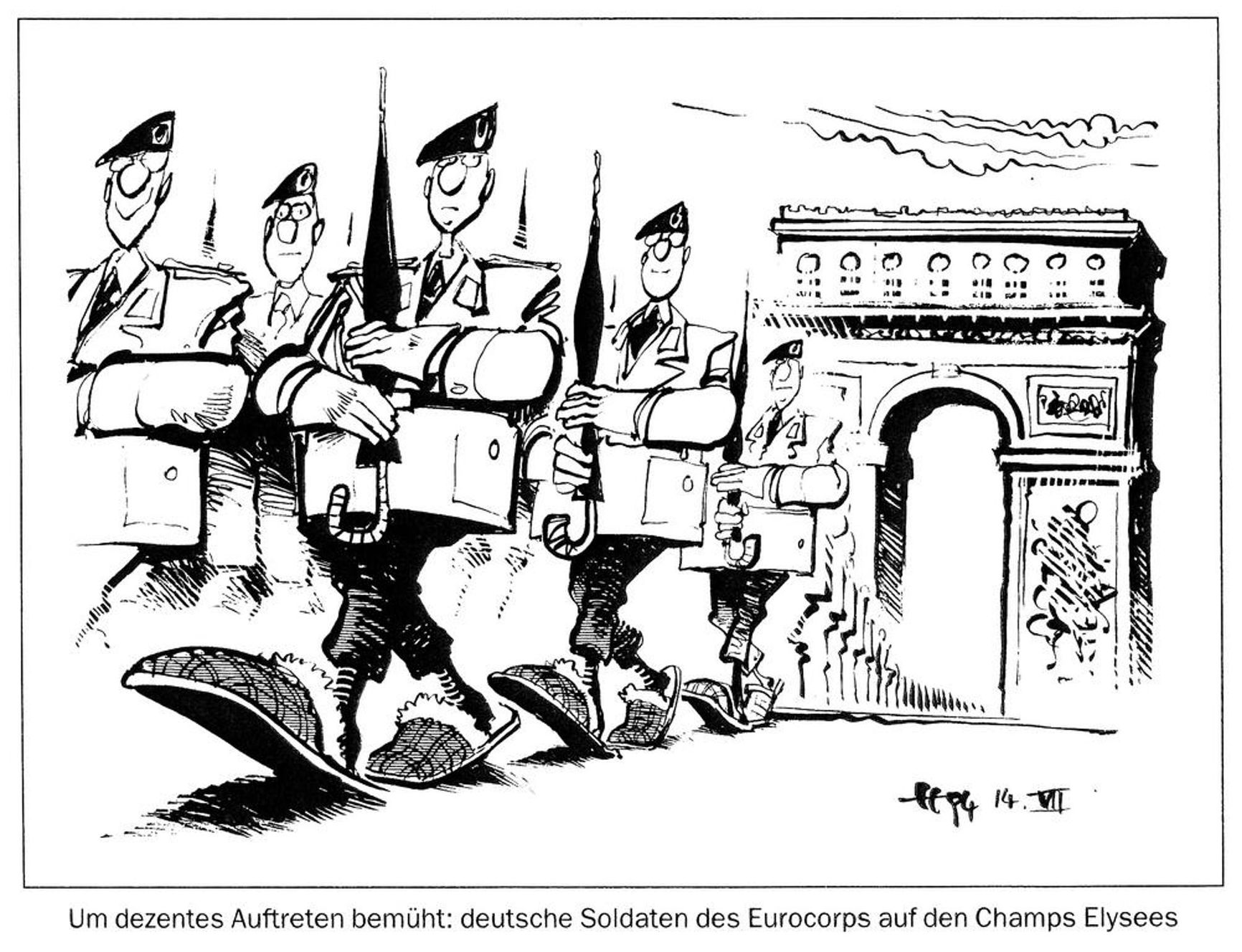

Amid these changes, symbols played an important role. In 1984, Mitterrand and Kohl had already sent the world a strong signal of friendship at Verdun, and now their successors continued this approach. In the 1990s, the Franco-German brigade became the foundation for the creation of the Eurocorps, while cultural projects, such as the ARTE television channel, reinforced the image of the two countries as the “engine of Europe.”

The peak of symbolic reconciliation came on July 14, 1994, when, for the first time, soldiers of the German Bundeswehr marched down the Champs-Élysées in Paris as part of the annual Bastille Day parade. For the French public, this was an unprecedented moment: the army of the country that had twice invaded France in the twentieth century was now walking down the capital’s main street as an ally. This parade served as a powerful confirmation that the fears of the past had finally given way to mutual trust and partnership.

Cartoon: “Trying to Make a Good Impression: German Eurocorps Soldiers on the Champs-Élysées,” 1994

Horst Heitzinger

Who is the enemy now? Sociology of relations

In the early years after the Second World War, French society regarded Germany as its main adversary. In a 1948 survey, 34 percent of French respondents called Germans “enemy number one,” while the USSR (22 percent) ranked second. But by 1954, the situation had changed: 57 percent saw the Soviet Union as the main threat, and only 10 percent cited Germany. At the same time, a 1956 survey found that nearly half of French respondents (49 percent) supported rapprochement with West Germany, although 36 percent still worried that the German mentality remained unchanged despite the demise of Hitler.

In Germany, public sentiment was shaped by harsh memories of the postwar French occupation. A 1950 survey by the Allensbach Institute showed that 65 percent of residents in the Rhineland and Saar considered their interaction with French troops to be bad, while only 8 percent regarded it as good. At the same time, Germans’ threat perception was focused in the opposite direction: in 1948, 79 percent considered the USSR the main enemy, while only 2 percent cited France.

Still, by the late 1950s, trust was beginning to grow among the French as well. In a series of surveys from 1958 to 1965, the share of French citizens with a positive attitude toward Germany rose from 32 percent to 47 percent.

A turning point came with the signing of the Élysée Treaty in 1963. More than half (54 percent) approved of de Gaulle’s policy toward Germany, and in a 1964 survey, 41 percent considered West Germany to be France’s best ally in Europe (compared with 37 percent who chose the United Kingdom).

By the 1970s, fear of the resurgence of a German threat had decreased further. In 1971, 41 percent of French respondents believed that Germany could again pose a danger to their country, but by 1973 this figure had dropped to 27 percent, while 57 percent rejected the possibility entirely. At the same time, most French people recognized that Germany was economically stronger than France (72 percent), and nearly half acknowledged that it played a more significant role in the wider world. Still, fifty-two percent of respondents were convinced that Germans were primarily focused on unifying their own country, which was seen more as a realistic prospect than a threatening one.

In the 1980s, West Germany had already firmly established itself in French perceptions as a privileged partner. In 1983, 48 percent of respondents named Germany as France’s main ally, compared with 33 percent for the United States and only 16 percent for the United Kingdom. At the same time, 63 percent of French citizens supported the idea of joint defense with West Germany.

By 1988, 54 percent of French respondents regarded Germany as their country’s “best friend,” while 67 percent of Germans named France as West Germany’s main international partner, up from 53 percent in 1983. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 was generally received positively in France: 66 percent considered German reunification likely, although nearly half (45 percent) would have preferred the process to proceed gradually.

By 1988, 54 percent of French respondents regarded Germany as their country’s “best friend,” while 67 percent of Germans named France as West Germany's main friend

Over four decades, French society moved from deep suspicion and stereotypes about the German mentality to a stable recognition of West Germany as its principal ally and partner in Europe.

The history of Franco-German reconciliation shows that it was not a single, instantaneous act that did the trick. It took decades to progress from the first personal meetings and courageous gestures of forgiveness in the postwar years to the creation of joint institutions, cultural exchanges, and symbolic acts of friendship. This process was difficult and often contradictory, accompanied by doubts, fears, and political crises. Yet it was precisely through the consistent combination of leadership diplomacy and grassroots initiatives that hostility was transformed into partnership.

France and Germany did more than overcome the past; they made reconciliation the foundation of a new Europe. Their alliance became a driving force of continental integration, and the experience of gradual rapprochement demonstrated that even the deepest historical wounds can be healed when societies and politicians work together.